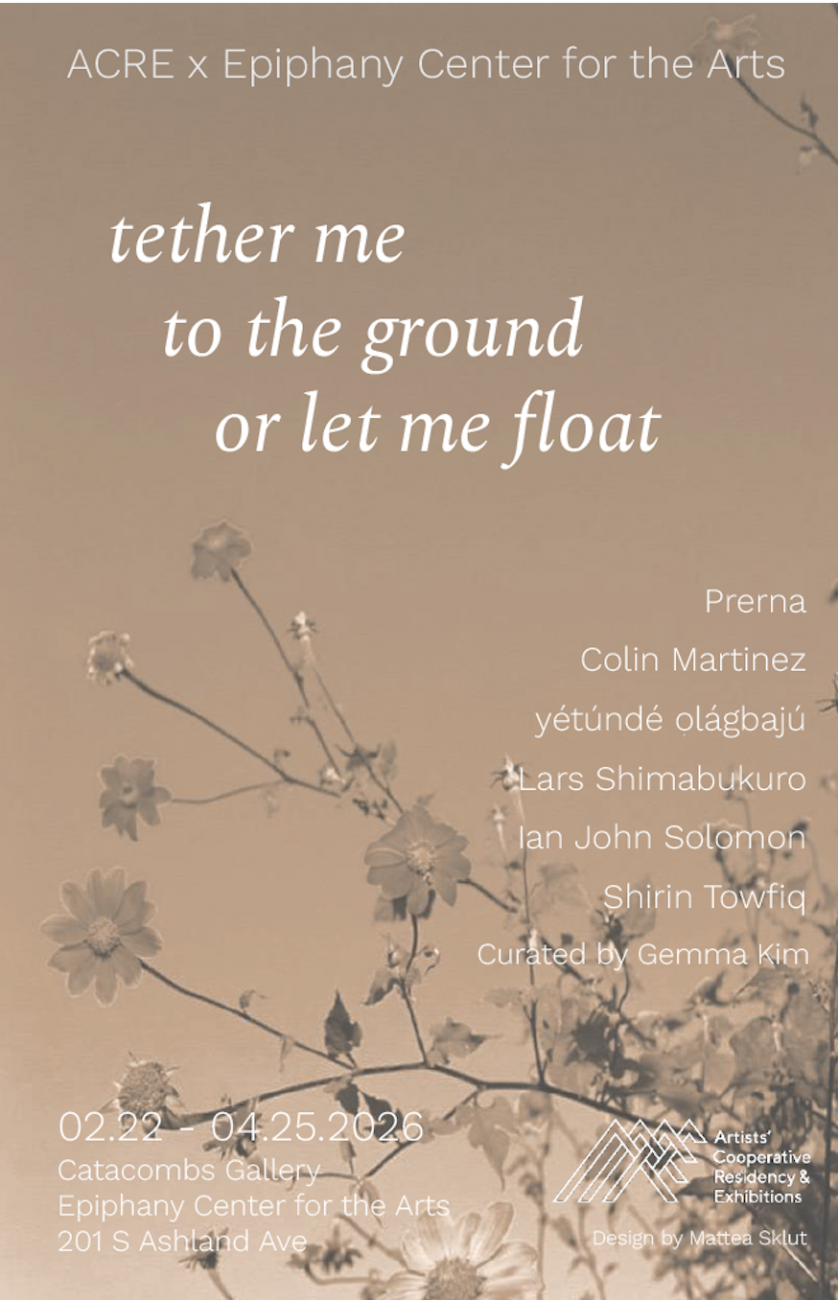

tether me to the ground or let me float

Curated by Gemma Kim

Epiphany Center for the Arts

Epiphany Center for the Arts

Opening Reception:

“We have been living in increasingly porous borderlands...” - Lucy Lippard, Undermining.

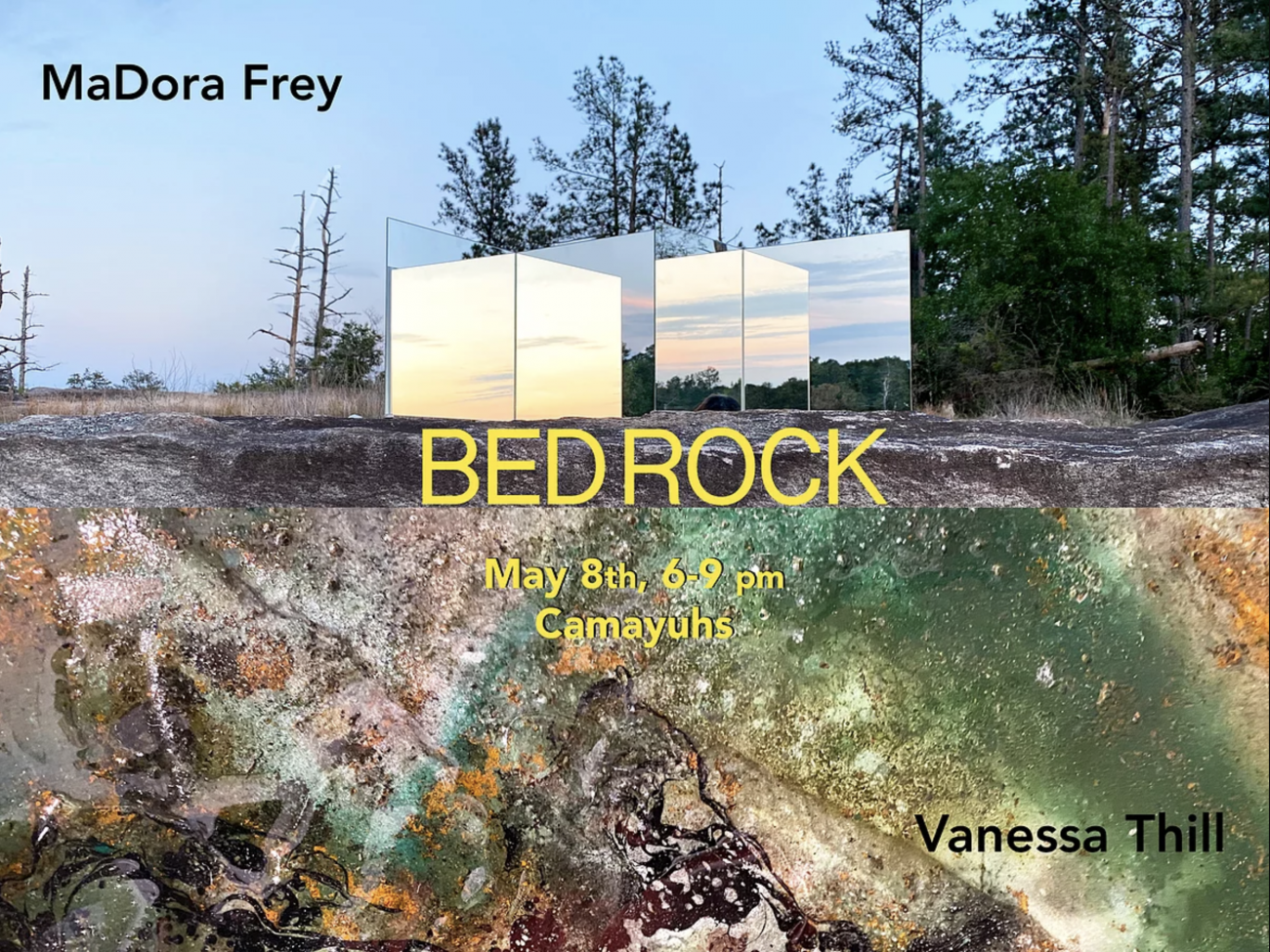

Via photo, video, and sculpture, MaDora Frey and Vanessa Thill explore themes of confinement of the body in quarantine and expose the layers of emotional and aesthetic resonance in our relationships to place. Frey and Thill were both influenced by Lucy Lippard’s book Undermining: A Wild Ride Through Land Use, Politics, and Art in the Changing West, which presents a collage of concerns about the ways humans intersect with nature. The artists were compelled by Lippard’s analysis of social systems through the lens of gravel, pits, and rock materials. She writes, “A gravel pit offers an entrance to the strata of place, suggesting some fissures in the capitalist narrative into which art can flow.”

Bedrock can be a strong foundation or a blockage of water flow and drainage. The exhibition title, Bed Rock, is meant to evoke some of these contradictions: ideas of excavation or revelation, a foundational core, discomfort at physical constriction or mental despair as in “rock bottom,” the domestic site of the bed, and the erotics of sublime nature. Both artists fixate on the symbol of the quarry, a place that epitomizes the extractive dynamics that have come to define our contemporary world.

Thill became interested in the phrase “angelic quarry” as it has appeared in Jewish mystical writings, referring to the source of life, endlessly springing from rock. To get closer to the divine, the Kabbalah tradition instructs to “cleave” to it, which means both to split and to join. While an angelic quarry is never-ending, human endeavors come up short, eventually exhausting mineable materials. The quarry becomes a site of quiet conflict, where an experience of nature is openly contaminated by the motives of racial-capitalism that repurpose so much of the world, and people in it, as raw material. To create the works on view, she uses a method of intentional contamination, submerging paper in a bath of natural pigments, metallic powders, salt, and sand, as well as spices, glue, soaps, and other household chemicals and foodstuffs. After the pooled liquids evaporate and crystallize onto the paper, Thill applies a resin coat, creating a kind of earthly dermis. The index of Thill’s body appears in her work Petro-Queen III, a hanging sculpture of crusted salts that renders her open legs and the void in between them as equally solid, equally riddled with holes.

Frey grew up on an abandoned quarry lake. As a girl, she ran through the overgrown rocky terrain not knowing that men had shaped this landscape too. It was only later that she learned its former use, and found a powerful attraction to the compromised yet awe-inspiring landscape. In response to the beauty and inherent destruction belonging to these natural wounds, she adopted devotional practices such as moving and arranging large quantities of rocks into patterns using her own body. In the works on view, Frey pairs human-made materials such as dichroic glass and reflective surfaces with available rubble, combining ingredients that are the detritus of the quarrying industry and millions of years of erosion with manufactured materials in impermanent arrangements. A photograph is all that remains of these transitory marks in spaces defined by the immensity of geologic time. Frey’s method of tapping into the sublime reminds us of our place in relation to the billions of years since the planet began, and consequently the forces greater than us.

The scale of the landscape dwarfs our delusions of grandeur, yet also reveals itself to be desperately fragile. By juxtaposing Thill’s and Frey’s work, we find a harmonious paradox between the problematic political implications of human interaction with the natural world and the sublime celebration of our transcendent experience with the same. As we consider these disparate yet connected works, we must ask ourselves: Who has claim to nature and an experience of transcendence through it?

Opening Reception: