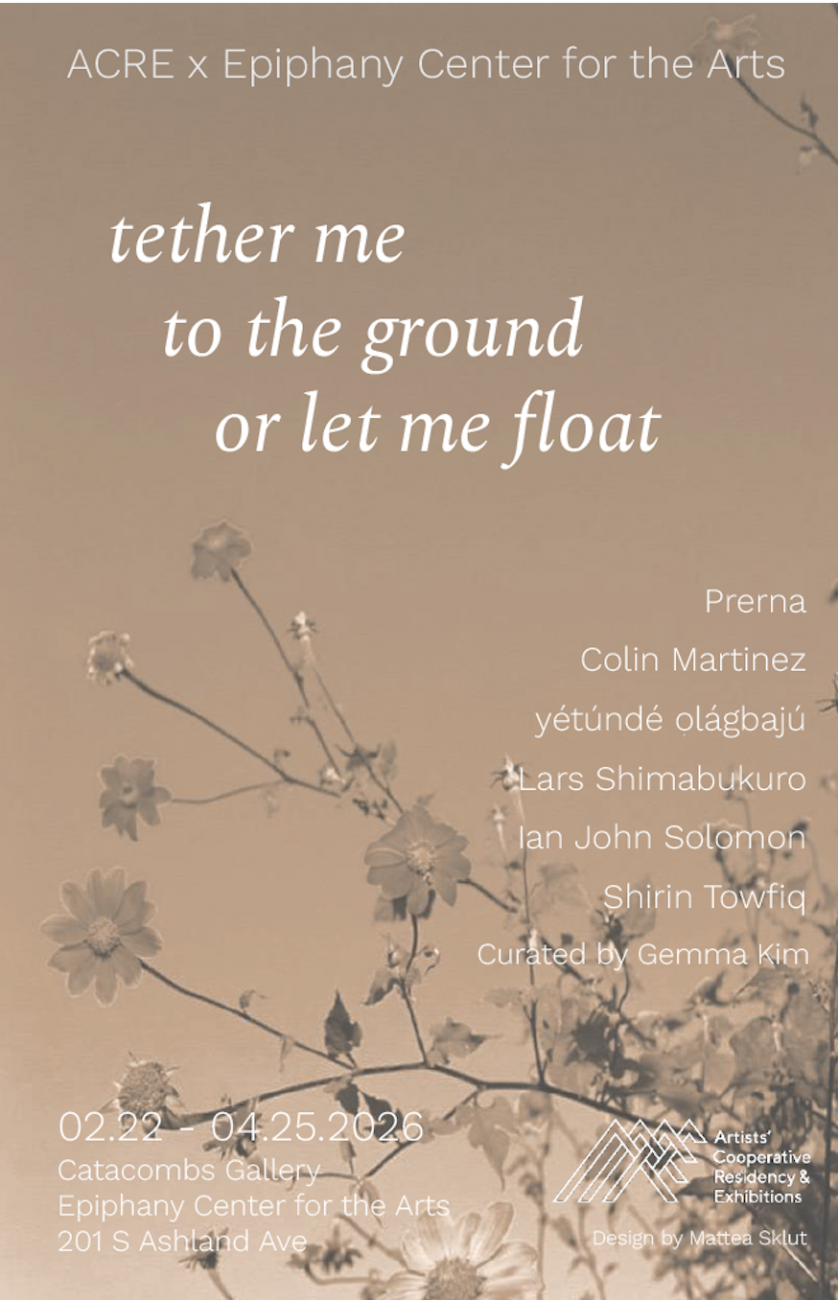

tether me to the ground or let me float

Curated by Gemma Kim

Epiphany Center for the Arts

Epiphany Center for the Arts

Howardena Pindell has been keeping receipts on racism and sexism in the art world for a long time. She has tracked the demographics of the artists shown at galleries and museums and documented where public funding has been used by art organizations openly discriminating against entire groups of people. “I feel that it’s important to cite facts and give credits so that people can hear or see that I am not the only one who acknowledges this information,” she has said. “I felt that keeping track of the racism needed to be done through counting. The numbers say everything.”

In our data-driven world, numbers are used more and more to make the case for important policy decisions. They tell us which workers have been most affected by the pandemic-induced recession, and whether the government response to helping those workers has been adequate. The Chicago Arts Census was born out of the knowledge that numbers talk, and that we need more data if we want to be able to make the case that the current art ecosystem in Chicago isn’t working for everyone.

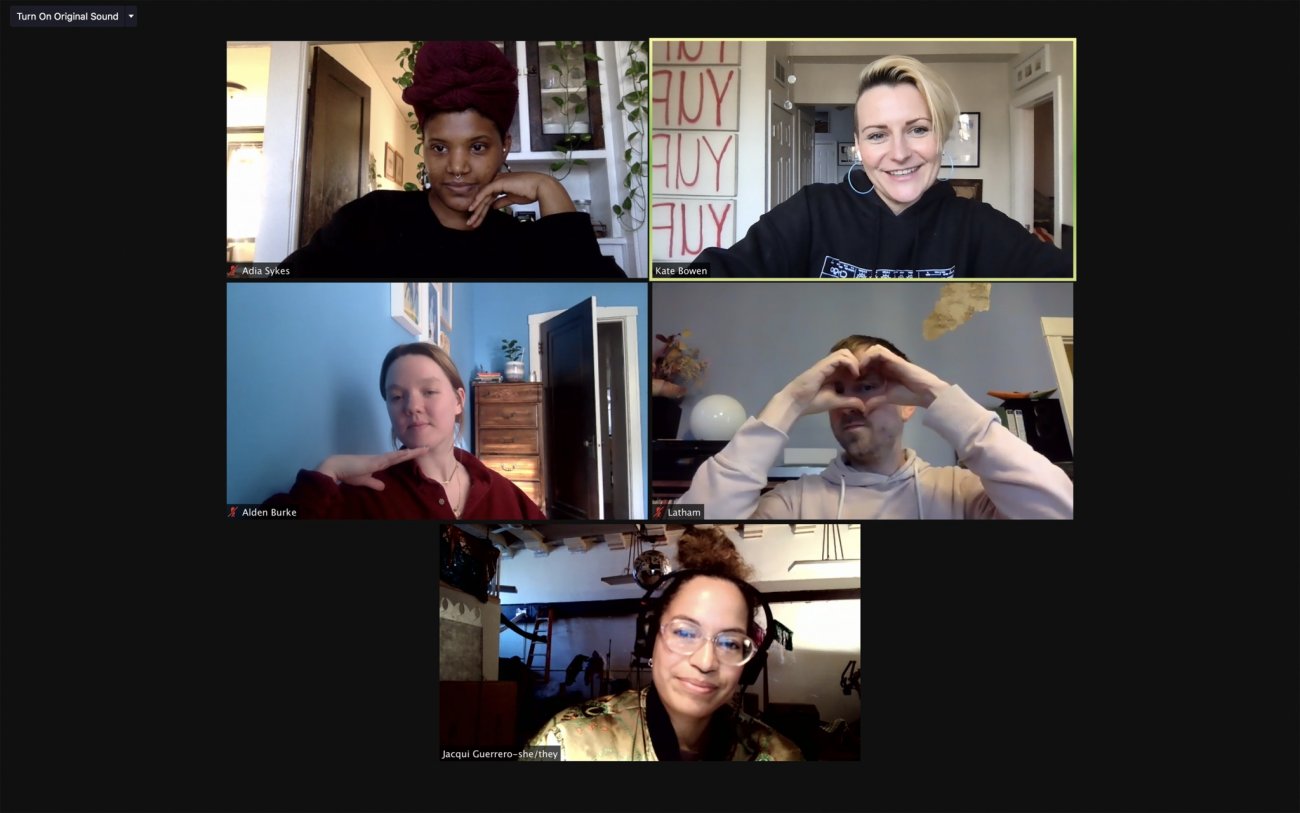

Early on in the pandemic, when Chicago was under stay-at-home orders, Kate Bowen, Adia Sykes, Stephanie Koch and Alden Burke started casual Zoom conversations every Sunday, taking stock of how to pivot their work and lives in the face of uncertainty. They realized that their peers in the art community were having a hard time thinking about programming and exhibitions while also figuring out how to pay bills or get healthcare, since the pandemic struck people’s income in so many different ways. They wanted to find a way to be useful, but there was no readily accessible information as to what might be of use to arts workers. Those conversations turned into the idea of a census of the city’s arts community, to collect real data on people’s lives and livelihoods, on what resources exist and what resources are still required.

Bowen, who is executive director at ACRE (Artists’ Cooperative Residency and Exhibitions), an artist-run nonprofit that provides resources to emerging artists, felt disconcerted to once again watch the bottom fall out of the economy. “There’s nothing here to hold us,” they say.

The four spent much of the past year planning and preparing the census project, which is slated to open in August. Funding received from the Arts Work Fund and the Walder Foundation also allowed the group to bring on a program manager, Tiffany Johnson. Part of that prep time was spent ensuring that stakeholders from many parts of the arts sector had the opportunity to provide input, to balance out the fact that the lead organizers all have visual arts backgrounds. Also integral to the rollout was infusing the project with an ethic of care, not wanting the questions to feel extractive or triggering. That desire has shaped every step of the project, from the way questions will be framed, to how it will be disseminated, to how the data will live once collected.

Outreach is a crucial factor; the potential for using the data to change the art world is only as good as the information collected. Folks will be able to take the census online as well as at in-person events throughout the city. “A lot of the work that we’re trying to do now is to identify and define and create the implications around which this information doesn’t exist,” says Burke, who cofounded the multi-platform project Annas along with Koch. “Data on arts workers and labor and livelihood hasn’t been collected in Chicago. So how do we now take this time to really share that information, and share the impact of what it means for arts workers to use the census?”

Sykes, an independent curator and administrator, says the use of the term “arts workers” was purposeful. “We’re very interested in preparators and fabricators and the docents who give you tours at any institution, and the security people who hear a lot of conversations and see a lot of things but again are never quite surveyed for the labor that they do,” Sykes says. “The term arts worker in itself, intentionally using that as opposed to artist or maker or something like that, is to kind of bust open the idea that we are all included in the same economy and contributing to its health and should all be supported as folks doing the labor as such.”

Another principle guiding the project is the philosophy of abundance, that there are enough resources to go around and that arts workers and organizations don’t have to be in competition over those resources. “We would look for the opportunity to build coalition, to be in support of one another, to share what we were doing as a way of also building power,” Bowen says. This is how the Census organizers teamed up with the Chicago Park District’s Cultural Asset Mapping Project (C.A.M.P.). C.A.M.P. kicked off in 2019, as part of the city’s Year of Chicago Theater initiative. The project is a community storytelling and data visualization project, intended to “better understand artistic excellence and cultural vibrancy in our communities.” The website offers resources including a community-sourced map of different cultural assets across the city and stories about the importance of those people and places. While the projects overlap in some ways, they also function in distinct ways. Both groups felt that working together would make their projects stronger. “It’s been a very nice experience to build this camaraderie,” Burke says. The collaboration is one way they are modeling how to be more abundance-minded.

“By jumping into this river with people doing similar work and having similar discussions, all that we’re actually doing is finding ways to augment the discussions that are already happening and together create this resounding chorus that will bring about some change,” Sykes says.

Once the data from the census is aggregated and further anonymized, it will be publicly accessible. In addition to issuing a formal report, there will be a data visualization tool, a bibliography and literature review, and published interviews with folks involved in the project, among other tools that can be used to spark change.

Bowen hopes the project can influence people working across the arts sector to understand that we are all workers. “I think that artists understanding themselves as the same part of an ecosystem as those who are working in the arts is one big thing,” they say. “I would really like to see funders or the city itself looking at ways to support artists that are not in the category of individual grants or projects that enliven the visual culture of the city. I think that we need some human resources inside of the arts that would really benefit us all.”

Burke envisions the project both continuing in Chicago and taking on iterations in other cities. “This project is so specific to Chicago and feels so infused with Chicago’s ethos and history, but the questions that we are asking are very universal,” she says.

All come back to the idea that the data can be used for advocacy, that it can be used as proof of what changes need to be made. “One of our other tenets and drivers of this is hope,” Sykes says. “And the very firm belief that this ecosystem can function in a way that supports us all in an equitable and liberatory way.”

“The last thing in our FAQ, in our manifesto-y first portion of it, the very last sentence is: We don’t want to go back to normal,” she continues. “Because normal isn’t working for all of us. And I think this past year especially has very much unearthed that fact. How then do we work toward creating that radically different future?” The Chicago Arts Census, one hopes, will be a useful tool in that journey.